On Age and Experience…

Mr. David Newton posted an enlightening piece to ESPN.com about the age of drivers in NASCAR. The author cites that the average age of the current top ten in the season-long standings is four years older than in 2008. Newton opines that this upward trend of age in the Cup Series’ stars will continue and that the league needs a “young, hot superstar.” He also outlines NASCAR’s strategy to combat the potential aging phenomenon by lowering the age-limit in developmental series.

This was an interesting article and it prompted two questions from me:

1. Do fans even care about “fresh faces” and young drivers in the Cup series?

2. From a macro-prudential standpoint, why can’t the current crop of developing drivers crack the Cup Series?

I’m legitimately curious about whether a younger, newer group of competitors in NASCAR attracts a greater household audience. To this point, I’ve only read anecdotal evidence of this relationship; of course, my first language is mathematics, so I compare the actual data to all of these narratives.

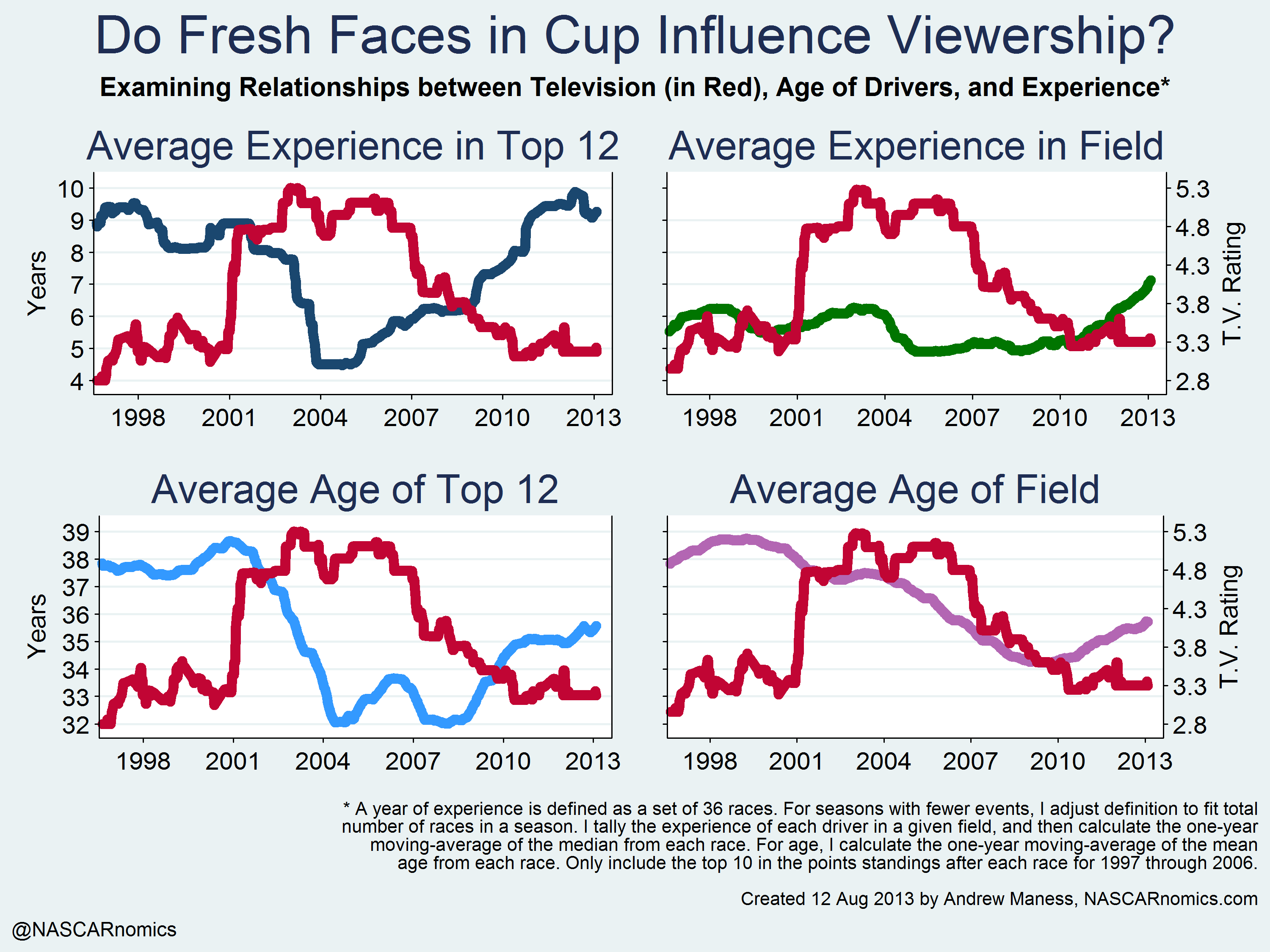

I plot four graphs in the next figure. They all compare a measurement of “youth” among drivers in the Cup Series to the league’s average television ratings (lined in red). The top-left window compares television ratings to the average years of experience for drivers in the top twelve in the season-long points standings after each event (blue). The top-right compares ratings to the average years of experience throughout the entire field (green). Similarly, the bottom-left chart analyzes the relationship between television ratings and the average age of drivers in the top twelve in points (light blue). Finally, the fourth graph assesses the average age of the field (purple) against television ratings:

It’s apparent that the experience or age of the entire field (the two right-hand graphs) does not influence television ratings. That observation makes sense to me; for the most part, casual viewers are unlikely to focus on the drivers churning in the 25th or 30th position (no matter the skill or experience those competitors possess). The average age of Cup’s “stars” in the bottom-left chart seems to move in the opposite direction of the household audience size. Similarly, the average years of experience among the top twelve in the season-long standings possesses the strongest negative relationship with television ratings for the Cup Series. From the graph on the figure’s top-left, “star” drivers accumulate experience from 2005 through 2012 as television ratings decline; perhaps, the presence of the same handful of competitors becomes a bit stale after appearing for weeks at a time for nearly a decade; the current average service time among “stars” is 9.5 years.

Of course, there are plenty of factors that correlate with NASCAR’s household audience. Over-the-air races, cable race, night-time events, and so many other variables play a role for the Cup Series’ television ratings. I want to account for these various changes and single-out the effect that each year of additional experience for “star” drivers has on NASCAR’s audience. I use regression modeling to neutralize all of these impacts and highlight in yellow the “star experience variable.” I explain what this means after the chart:

(You can view the entire regression model here.)

(You can view the entire regression model here.)

After accounting for all of those factors that contribute to NASCAR’s television ratings, each year of experience (shaded in yellow) among Cup’s stars reduces the household audience by 0.6%. In general, that exposure of the same “stars” may become superfluous. Indeed, fans are negatively influenced by the average experience and age of ”star” drivers. Generally, fewer folks are willing to watch a race if it includes a similar pool of frontrunners for a long period of time.

I’ve empirically proven that fans do care about having a younger or newer group of drivers toward the top of the season-long standings. But what’s keeping that from happening? Mr. Brad Keselowski provides his insight on the issue:

It’s getting older. To be quite frank, I don’t see a lot of turnover coming because I don’t see a significant crop of young drivers that are better. It’s probably less than three or four drivers that I see being able to make it in the next decade. I don’t foresee the average age getting younger.

Aside from the ever-subjective discussion of which competitors are “talented” enough to hack it in the top stock-car series, I report another reason. The following table outlines four scenarios that influence the number of “fresh faces” in the Cup Series. Yes, there are other reasons; but I believe these specific events to be driving the current lack of new talent in NASCAR:

I initially focus on box “1″ — this cycle normally occurs throughout the history of NASCAR’s top series. Full-time drivers gain experience and simultaneously grow older. I split that effect into two basic parts:

I initially focus on box “1″ — this cycle normally occurs throughout the history of NASCAR’s top series. Full-time drivers gain experience and simultaneously grow older. I split that effect into two basic parts:

- As competitors gain more experience; drivers accrue talent, protect their jobs, and create fewer opportunities for new men and women in the Cup Series.

- Against that effect, however, those same competitors approach retirement-level as they gain that skill. With an aging field, potential rookies do not have to wait as long to crack the top series.

The result of these two concurrent events is a constant cycle of drivers of all ages and experience. It provides “young guns” and “cagey veterans.” (Why am I using those terms? Because I’m lame, I guess.) The major issue that the Cup Series faces right now is the impact of that second bullet-point — NASCAR’s top-level teams, in general, made a push in the late-1990s through the mid- and late-2000s for historically young talent:

The taupe line displays the standardized average age for the field in the modern era. (0.0 represents the average age and experience level; values above 0 indicate above-average age and experience of the entire field.) That push for younger talent drove the mean age in races to a historical low by the end of 2009. Meanwhile, the average experience-level over the entire competition didn’t drop as much. Since the “hiring period” of several new drivers lasted for a decade (approximately beginning in 2000 and ending in 2008), the rookies on the front-end — such as Dale Earnhardt, Jr., Kevin Harvick, and Kurt Busch — gained enough experience to off-set the lack of experience by younger guys on the back of this phenomenon (i.e., Kyle Busch, Denny Hamlin, and Martin Truex, Jr.) by the end of that time. The outcome of a prolonged period of grabbing historically young drivers led to a “bubble of youth” in the late 2000s; as a result, NASCAR is stuck with an inordinate gap between the average age and experience of its drivers. The light-blue area of the previous graph depicts this rift between experience and age.

The taupe line displays the standardized average age for the field in the modern era. (0.0 represents the average age and experience level; values above 0 indicate above-average age and experience of the entire field.) That push for younger talent drove the mean age in races to a historical low by the end of 2009. Meanwhile, the average experience-level over the entire competition didn’t drop as much. Since the “hiring period” of several new drivers lasted for a decade (approximately beginning in 2000 and ending in 2008), the rookies on the front-end — such as Dale Earnhardt, Jr., Kevin Harvick, and Kurt Busch — gained enough experience to off-set the lack of experience by younger guys on the back of this phenomenon (i.e., Kyle Busch, Denny Hamlin, and Martin Truex, Jr.) by the end of that time. The outcome of a prolonged period of grabbing historically young drivers led to a “bubble of youth” in the late 2000s; as a result, NASCAR is stuck with an inordinate gap between the average age and experience of its drivers. The light-blue area of the previous graph depicts this rift between experience and age.

Now the Cup Series has the dilemma of a relatively young group of veterans with the most experience of all-time. Why is this a predicament? Box “3″ from my table elaborates. The current set of Cup drivers continues piling-up experience, talent, and face-time — the perfect ingredients to protect their jobs (or, at least, a spot in the field). Thus, opportunities to advance diminish for drivers in developmental series. Simultaneously, drivers are maturing; but they are still below the average age of the traditional Cup field. Without retirement on the horizon for many of these highly-experience competitors, the wait-time for developmental drivers is lengthy. Ultimately, this means that there just isn’t much room for new talent to join the Cup Series (short of new teams and sponsors joining the fray).

As with any sharp change in behavior, the “bubble of youth” will correct itself over time. How many years must elapse, though, before a consistent batch of fresh faces pops-up every season or two? I don’t know. The glut of young- and medium-aged drivers with hundreds of races under their belts is large. Unless many of them retire early, I agree with Mr. Brad Keselowski’s analysis. There are plenty of reasons for why several promising drivers are having trouble advancing to Cup — sponsors and talent obviously play a role. The analysis I’ve posted intends to supplement those theories.

Once again, thank you so much for reading. This has been a fun ride. Feel free to chime-in on the discussion via electonic mail or Twitter. You can send me a tweet at or send me deeper thoughts via electonic mail at . Additionally, if you have any questions or research you want me to conduct, let me know.