On Starting-and-Parking…

[NOTE: This entry is a bit long, but it's straightforward with plenty of graphics to create intriguing perspectives. As I always emphasize, my research intends to supplement -- not reject -- anecdotal evidence provided by those in industry. Mr. Gossage, the inspiration to this article, has a much different job than mine. While he often must answer questions on-the-spot and without notice, I have the luxury of several months to research and craft a conclusion. Please keep that in mind.]

“Starting-and-parking” has occurred in NASCAR for several decades, but has recently taken ahold of the back part of the weekly field in the Cup Series. The term describes any team that enters and starts an event for the sole purpose of reaping the financial benefits associated with participating in a race. Since these organizations’ objectives do not include optimizing their position in the field, they typically cut costs by retiring shortly after the initial green flag. The purpose of this research is to examine how these operations affect those watching races at home, those attending NASCAR events, and the actual tracks themselves. (The credibility of these teams has been questioned in recent years. I do not resolve to condemn or support starting-and-parking; I’m not an authority in that discussion.)

Texas Motor Speedway president Mr. Eddie Gossage provides his views on “starting-and-parking:”

The start-and-parkers are simply stealing . . . [T]hey are going to steal a half a million dollars [at Texas] . . . People are stealing in broad daylight in front of 150,000 fans in the grandstands and millions of people watching at home.

To illustrate, Mr. Gossage notes that NASCAR paid about $17 million in 2012 to start-and-park operations in the Cup Series. (I actually calculate that to be much lower — about $13 million, or 6.7% of the $194-million tour). The track president suggests that events on the schedule exclude prize payment to the bottom six finishers. The money saved would be dispersed to the rest of the field. This is an important issue for Mr. Gossage, as his track annually raises the third- or fourth-largest purse on the Cup Series calendar.

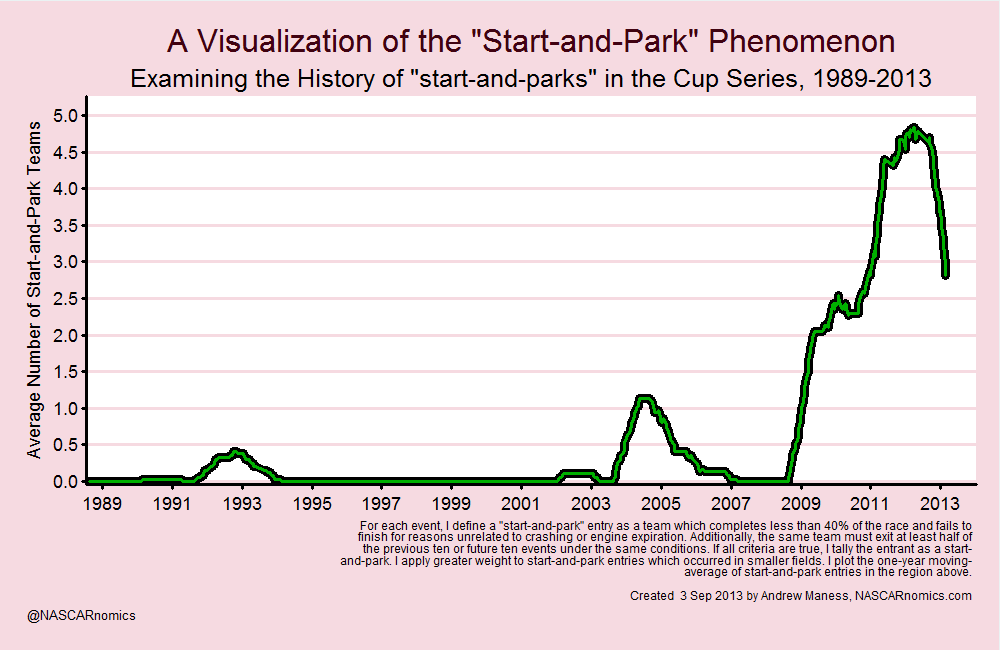

I empirically define a start-and-park organization. First, I identify all race entrants which complete less than forty percent of the race. The team must also retire early due to something other than a crash or expired engine. Among those competitors, I single-out out teams which fit those criteria for at least half of the events in the previous ten and future ten races. Any entrant that fits all criteria and exhibits that pattern over a twenty-race stretch is tallied as one start-and-park entry. While this algorithm may be imperfect, the following graph demonstrates that it is strongly enforced by most anecdotal evidence:

Starting-and-parking has been around for awhile, but it’s been relatively prevalent since 2009. Most recently, however, the number of early retirees in each race has decreased in 2013. Notably, this year’s edition of the Brickyard 400 tallied forty-three finishers out of a possible forty-three. (That’s the first occasion of zero-attrition since late 2008.)

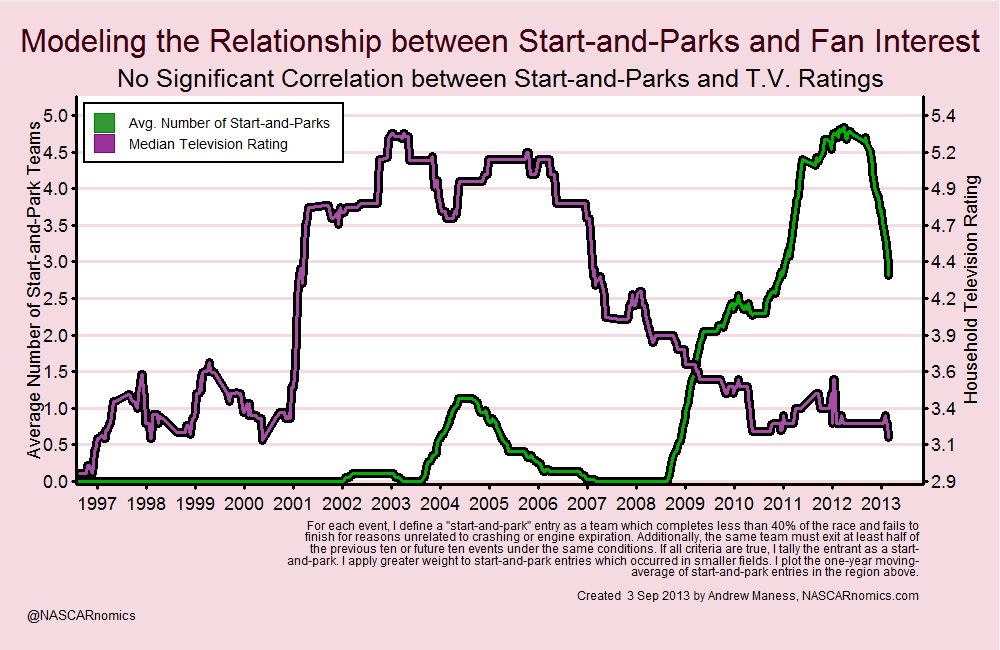

So how does this affect the folks watching races at home? Very insignificantly, as you would expect by the graph below:

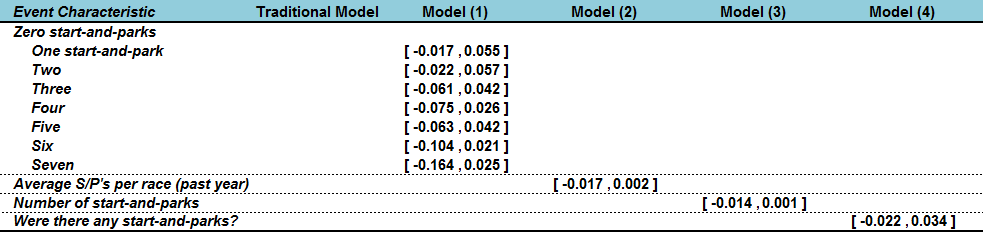

Obviously, the average number of start-and-parks (green) increases in early 2009, but the median television rating (purple) decreases by 25% before starting-and-parking was even re-introduced that year. To statistically determine if there is an effect, I gather several precise measurements to confirm my suspicions that there’s no reaction from a television perspective. I test four versions to determine whether there’s a robust correlation. After I hold several other variables constant, I find there’s no relationship between the number of start-and-park entrants and the average household audience:

(You can view the full results for all five models here. You’ll see all of the variables that I take into account, including T.V. network, track configuration, and a host of other characteristics.)

For each model, the impact of the prescribed “start-and-park measurement” on television ratings is listed as a confidence interval. The actual impact of each start-and-park calculation lies somewhere between the two numbers in brackets. None of these models indicate that the actual effect is greater or less than zero. Thus, I conclude that this phenomenon has no effect on NASCAR’s television ratings. This is not surprising. With or without start-and-park efforts in the field, most telecasts focus toward the front of the field. The last handful of positions are rarely observed.

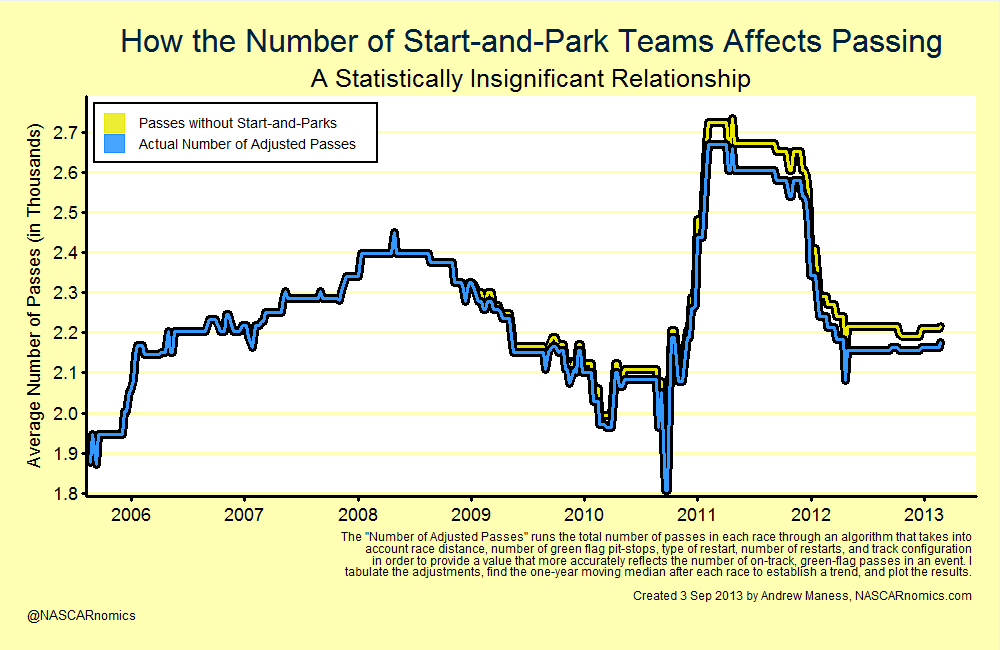

But what about the fans at the race-track? Wheeling a car into the garage in the early segment of an event can be witnessed at the facility. Although it’s difficult to measure how starting-and-parking affects attendance (I outline the reasons for that here), I can measure its impact on passing. Many people who view a race in-person a race may judge the “entertainment value” of the event from the number of green-flag passes that they observe. I check whether the number of start-and-park entries in a race significantly affects the number of passes in a race:

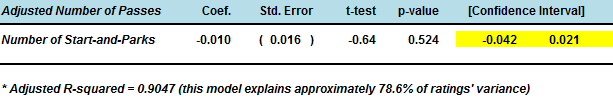

The blue line represents the actual number of adjusted passes from 2006 through today. Meanwhile, replacing start-and-park entrants with teams planning on finishing the race is highlighted in yellow. This particular visualization demonstrates that start-and-parks do not significantly detract from the “entertainment value” of a race. At its peak in 2012, fans witnessed less than 100 fewer green-flag passes per race because of starting-and-parking. Specifically, an individual start-and-park entry has no significant impact on the number of adjusted passes historically:

Note that the statistical “truth” lies somewhere in the highlighted confidence interval. That value could be either positive or negative; the number of start-and-park entries has no statistical impact on the adjusted number of green-flag passes in a race. This is fantastic news — fans should not have to worry about whether they are missing-out on additional competition due to this recent NASCAR phenomenon.

Note that the statistical “truth” lies somewhere in the highlighted confidence interval. That value could be either positive or negative; the number of start-and-park entries has no statistical impact on the adjusted number of green-flag passes in a race. This is fantastic news — fans should not have to worry about whether they are missing-out on additional competition due to this recent NASCAR phenomenon.

And finally, I assess how Mr. Gossage’s suggestions would affect NASCAR’s tracks and teams. Texas Motor Speedway’s president offers that the purse be withheld from the bottom half-dozen finishers. Alternatively, that money would be distributed to the first thirty-seven at the end of the event.

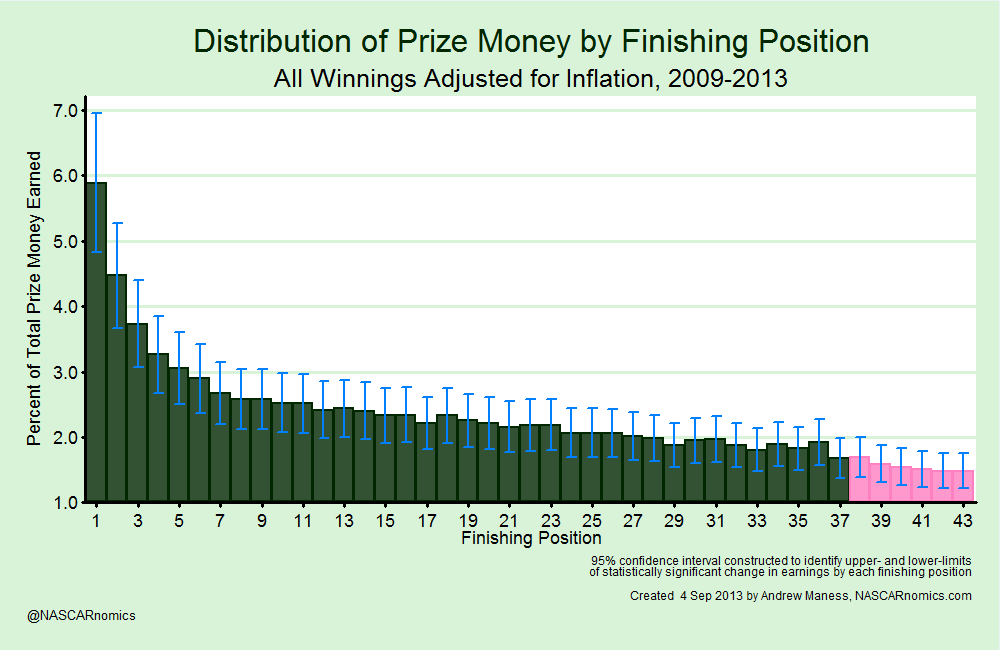

I present the average purse share by finishing position from 2009 through today — the time period of the recent start-and-park phenomenon. (These average values were adjusted for inflation, Mr. Dutton.) I highlight in pink the positions that Mr. Gossage cites in his discussion:

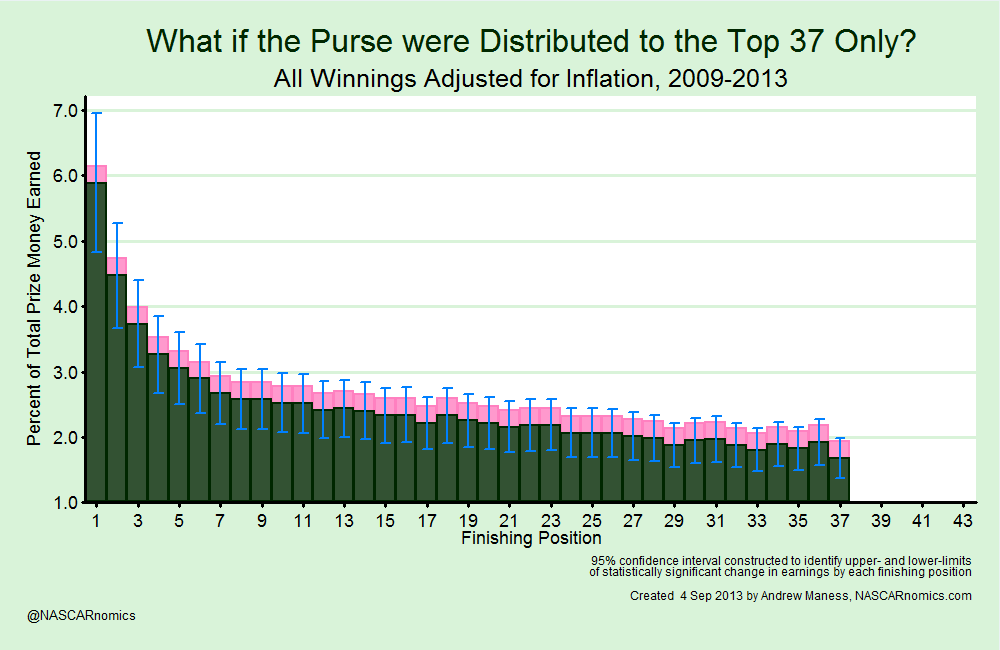

Each light-blue line represents a statistically significant change in prize-money share. For example, the average share earned by 35th place in a given Cup race is roughly 1.8%. A track would need to sweeten the pot for that finisher by about $16,000 in order to change meaningfully (from a statistical perspective) the prize money that team received. While this confidence interval doesn’t matter as much for the front-runners in a field (as they typically have diversified sources of revenue), this change is important for small teams which rely more on weekly prize money. What happens if tracks refuse the purse from the bottom half-dozen finishers and distribute that ten-percent share to the first thirty-seven? I highlight in the pink the additional earnings for each position:

The chart above shows that re-distributing the purse from the last half-dozen finishers does not create meaningful statistical change (as represented by the pink share never exceeding a blue line). Meanwhile, the bottom six participants earn 0% of the prize money. Overall, Mr. Gossage’s skewing idea would help neither full-race competitors nor start-and-park organizations.

Starting-and-parking has existed in major motorsports series for several years. It’s a source of much debate in NASCAR. I have no “side” in that argument; it’s largely an issue of morality, in my opinion. My intention of this research is to present the effects of early retirees on the fans at home, the folks in the stands, and the teams and tracks themselves.

Thanks for reading. I hope that this stuff makes sense. If it doesn’t, please tell me! The last thing I want to do is confuse anybody about a sport that is supposed to be fun. You can issue me a tweet at or send me deeper thoughts via electonic mail at . Additionally, if you have any questions or research you want me to conduct, let me know.