On the NFL Dilemma…

For almost two decades, NASCAR annually reaffirms itself as the second-most watched sports series in the United States. And while that claim is widely debatable, the National Football League remains the undisputed most popular league. Even though the ability to watch NASCAR and the NFL simultaneously is gradually expanding through various second-screen efforts (or maybe not), most households prefer watching professional football over motorsports if forced to choose only one. In this entry, I calculate by how much the NFL deteriorates the Cup Series’ ratings and provide policy analysis to resurrect NASCAR’s late-season ratings.

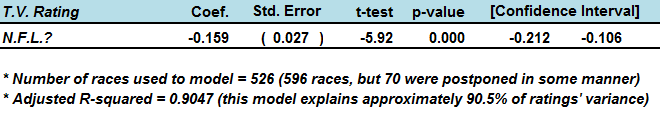

I begin with the NFL portion of my model to examine how it relates to NASCAR’s television audience. Clicking on the table links the reader to the entire model so that he or she can examine how different event characteristics marginally impact the Cup Series’ television ratings from 1996 through 2012:

The coefficient reports that any race competing with a professional football game results in a 15.9% deduction of its household audience, ceteris paribus [ 100 * -0.159 ]. For example, the 2012 fall Phoenix race that draws a 2.8 rating hypothetically earns a 3.2 if the NFL does not host a set of games overlapping with the NASCAR event (this translates to roughly 600,000 households). But I am curious about the NFL’s impact on the Cup Series’ ratings over time. To analyze, I create a set of interaction terms in my model to determine the impact of professional football competition within each television contract. My results are listed below:

The coefficient reports that any race competing with a professional football game results in a 15.9% deduction of its household audience, ceteris paribus [ 100 * -0.159 ]. For example, the 2012 fall Phoenix race that draws a 2.8 rating hypothetically earns a 3.2 if the NFL does not host a set of games overlapping with the NASCAR event (this translates to roughly 600,000 households). But I am curious about the NFL’s impact on the Cup Series’ ratings over time. To analyze, I create a set of interaction terms in my model to determine the impact of professional football competition within each television contract. My results are listed below:

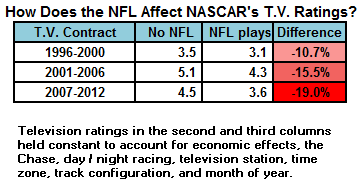

The second column lists the average rating of races that do not compete with the NFL (with other variables held constant). The third column displays the same for weekends in which NASCAR overlaps with professional football. The results from this table suggest that the NFL edges into the Cup Series’ audience increasingly with each television contract — from just 10.7% in the late 1990s to 19.0% under the current television structure. That is, professional football lessens NASCAR’s audience by nearly twice as much as it did thirteen-plus years ago. Furthermore, I conduct a year-by-year analysis to see which seasons suffer the most or least from competition with the NFL:

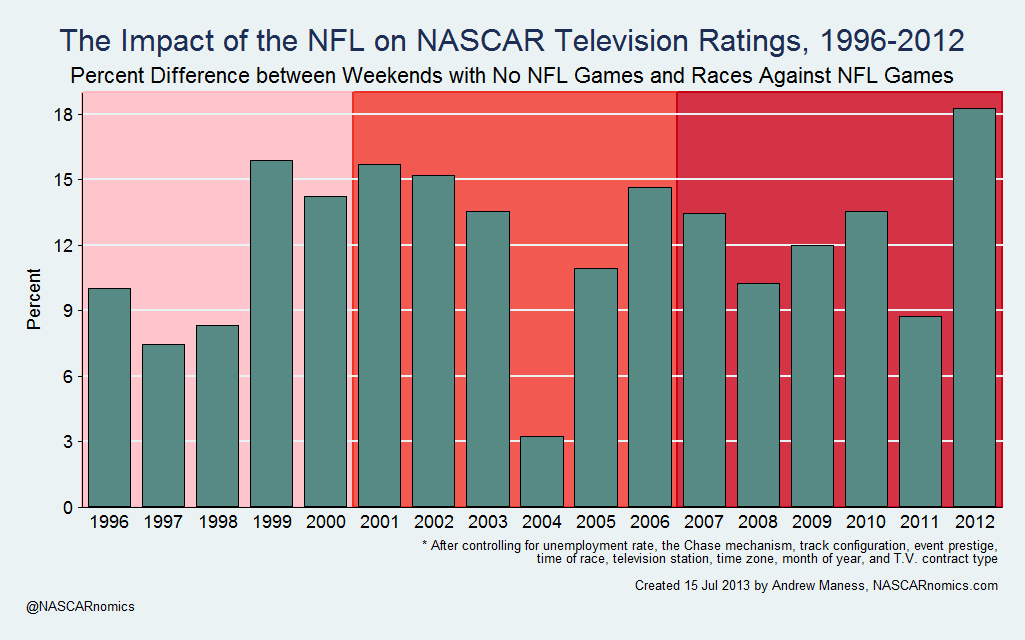

I shade each television contract (the darker the red, the more susceptible the Cup Series is to NFL competition). Each bar represents by how much race weekends with no NFL overlap exceed those against the NFL in ratings. That is; the lower the bar, the less professional football negatively affects NASCAR televised events in the given year. Since NASCAR implemented a postseason system, the penetration from the NFL depends somewhat on how the end-of-season points battle is turning out — a more intriguing championship battle may retain a larger motorsports audience (see: 2004 and 2011). As I wrote in a previous essay, the Chase has no affect on the Cup Series’ ratings in the long-run — this graph reinforces that idea; perhaps NASCAR does not achieve its goal of engineering a tighter end-of-year championship battle. Although the season-long points are reset in September, a ten-race playoff may provide ample time for one or two teams to lock-up a position in the standings with a a couple of races remaining.

So how does NASCAR’s top series avoid the “NFL dilemma” in the fall? Here are just a few options:

- Keep working on the postseason system to ensure that a “barn-burner” occurs most seasons; perhaps a six-race playoff aids that endeavor. Such an adjustment could be tough, however, as many tracks rely on the Chase to advertise and sell tickets. Removing that recognition from a handful of facilities could carry the negative externality of disastrous attendance figures.

- Reduce the top series’ number of races in the fall by either contracting the schedule or hosting mid-week races during the summer. That option does not appear likely, though.

- Maintain the schedule framework; increase the household audience by holding more Saturday night races in the fall. Anecdotal evidence also suggests that attendance at the gate expands as well. I examine this option further.

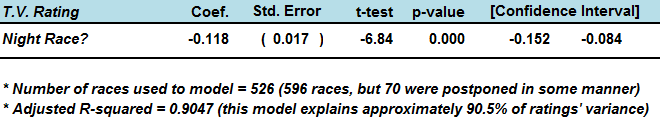

Recall that night events draw smaller audiences than races held on Sunday afternoons, all else being equal. But in the fall, “all else” is not equal; rather, the NFL dampens the would-be Sunday rating by 19.0% under the current television contract. Meanwhile, prime-time events only reduce a track’s potential rating by 11.8%:

In other words, running a race on a Saturday night in the fall theoretically out-draws a race on NFL Sunday by 7.2% [ 100 * (0.190 - 0.118) ]. While neither situation is ideal, night racing provides a better alternative for the television interest of NASCAR.

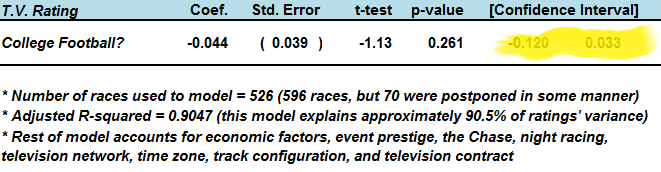

One common objection to this methodology includes the traditional college football schedule. The Cup Series may worry about several NCAA games clogging the television waves on a Saturday night. To see if these top-level amateur events negatively affect NASCAR’s ratings, I test a variable in my regression model that includes thirty races (among all others from 1996 through 2012) which compete for viewership with Saturday night college football games:

Similar to my coefficient analysis on the Chase, college football games appear to have a negative impact on ratings in the Cup Series — the coefficient is -4.4%. But the confidence interval (shaded in yellow) notes that the model cannot provide conclusive evidence; the impact of college games on the Cup Series’ average television rating is somewhere between -12.0% and +3.3%. As such, college football has no statistically significant effect on NASCAR’s television ratings for the Cup Series.

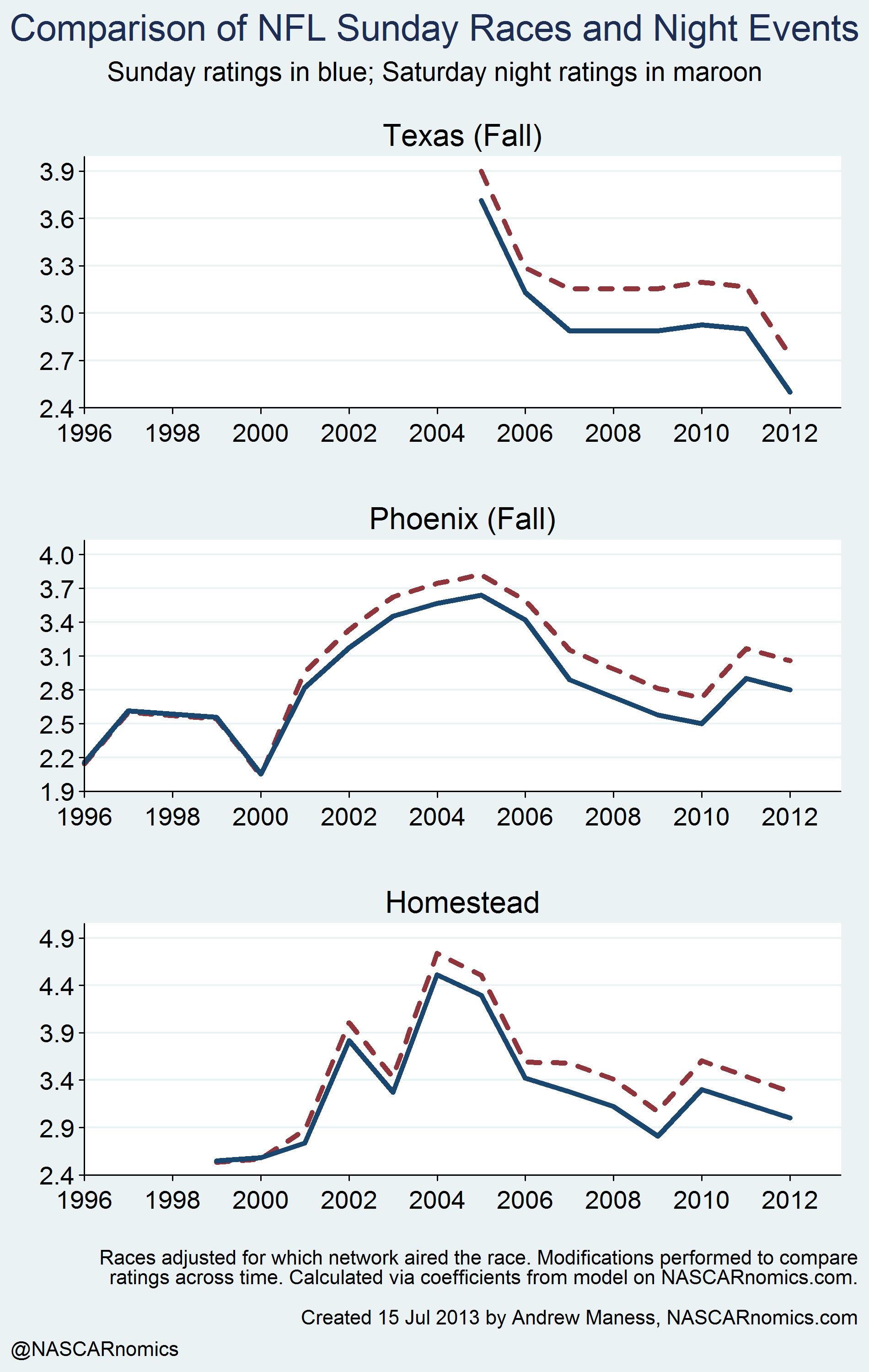

Okay. So what happens if NASCAR moves three fall races — Texas, Phoenix, and Homestead — to Saturday evenings? Let’s find out:

The realized Nielsen rating is plotted in solid blue, while the dashed maroon line charts the hypothetical Saturday prime-time event’s television rating. This figure is consistent with my previous assessment that the NFL eats away at NASCAR’s audience more now than in the past. In the late 1990s, for example, a Sunday afternoon event at Phoenix or Homestead performs on television as well as the hypothetical Saturday night race. In recent years, however, football excels on television; as a result, Sunday afternoons lose some luster in the NASCAR world. Thus, night racing is currently a more attractive option than competing against the NFL — it holds its value much better historically.

Obviously, there are some wrinkles with moving races to the evening. Which tracks can guarantee a comfortable climate? Even the most desirable locations are susceptible to cooler weather in October and November. Would NASCAR be willing to risk potentially going against a Southeastern Conference prime-time football game on CBS? What about running Cup Series races on a Saturday afternoon? I don’t think that’s a great idea (CBS usually televises the SEC’s top game at that time; ESPN has a full slate of games as well), but could it work? Would it be better than butting heads with professional football? It’s a tricky situation, but this post provides an additional option to NASCAR’s “NFL dilemma.”

Feel free to contact me via e-mail or Twitter with your opinions, comments, or questions. Here are links to each point of contact:

- You may contact me via e-mail at

- I hang out on Twitter and post some pretty cool graphs –

Thank you for reading. Please ask me all of the questions you have. I’ll do my best to answer them all.