On Diminishing Returns…

NPR’s Mr. Frank Deford theorizes that NASCAR’s overall decline in fascination is due, in part, to the “diminishing returns” on speed and how speed is “out of fashion.” I analyze those concepts and determine their validity. My research isn’t absolute; but it’s intended to spark more discussion on the original author’s accusation. You can click this link to review the author’s transcript.

(He also cites a couple of other reasons, but those are largely based upon interpreting automobile sales as “fascination” for cars; which is part of an ongoing debate that I won’t touch in this entry.)

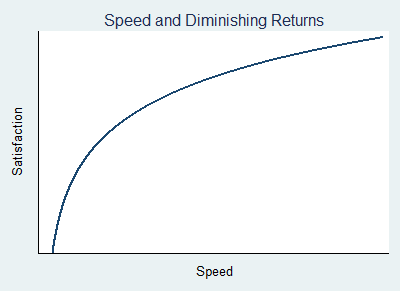

First, I illustrate the “diminishing returns” that are referred to in Mr. Deford’s piece. Imagine that I gave you a free candy-bar. You would gain a lot of happiness as a result. Now pretend that I gave you a second. How would you feel? Even more satisfied, of course, but not doubly. After all, you have to carry around an extra bar and you might get a stomach ache. Fast-forward to my giving you that one-thousandth candy-bar. Do you gain any satisfaction from that particular bar? Assuming that you can’t resell it, probably not. By this point, you’re sick from all of the previous candy, your medical bills have likely increased, and you’ve put on a lot of unnecessary weight. Although this example makes some assumptions (and actually describes “diminishing marginal utility”), I think it gets the point across and would be an agreeable example for Mr. Deford.

I transition that example to the world of motorsports. Mr. Deford’s theory is as racecars gain more speed, the population’s collective satisfaction doesn’t increase as much — “Speed up the game? No, the trick is to game up the speed” instead. For example, his notion of diminishing returns suggests that an increase in speed from 199mph to 200mph (999 to 1,000 candy-bars) doesn’t increase our happiness as much as an increase, say, from 189mph to 190mph (1 to 2 candy-bars) would. The following graph displays his theory:

This is a difficult opinion for me to analyze and dispute entirely. I don’t have the necessary data for other motorsports such as drag or formula racing. I can’t provide much useful analysis for anything before the 1990s; examining the desire for more speed must be restricted to a single time period. Television ratings are a reasonable gauge for NASCAR’s popularity, but conveying speed on T.V. emerges mostly from narrative. Seeing a race in-person, on the other hand, allows viewers to witness faster speeds; but attendance figures attract some trepidation.

So I quantitatively assess whether speed is actually “devalued” due to diminishing returns. In other words, I answer the following: “Collectively, does a population gain just as much satisfaction at Cup Series races from an increase in higher speeds as it does from an increase in lesser speeds?”

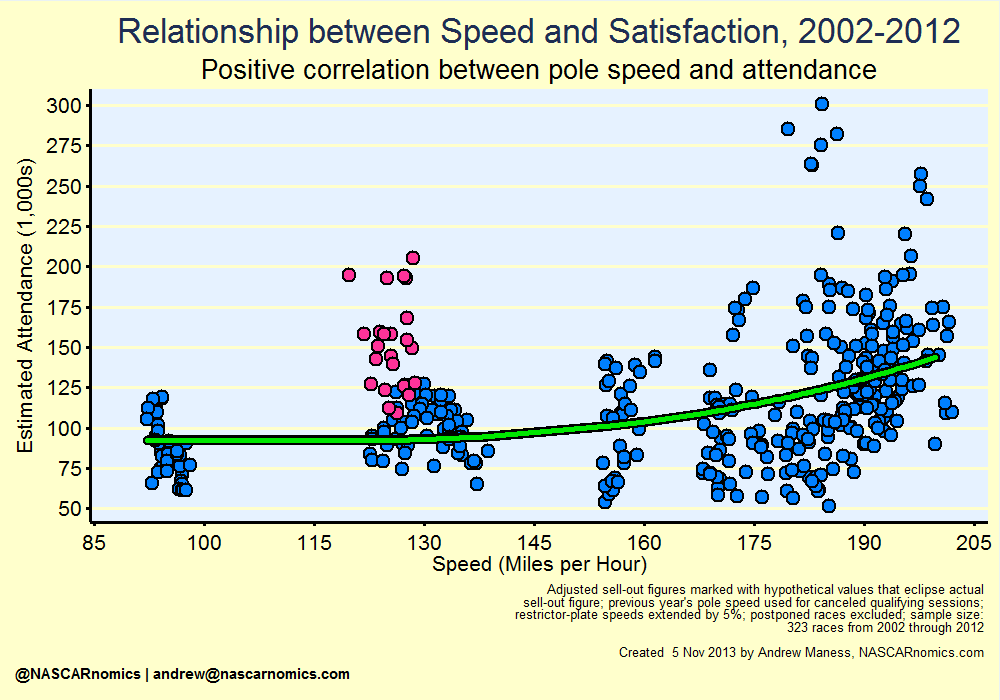

I conduct my experiment by gathering pole-winning speeds for all Cup Series races from the past decade. I use those values as a representation of “speed.” For races in which qualifying was canceled, I incorporate that event’s pole speed from the previous year. I extend restrictor plate pole speeds by 5% to simulate the drafting effect that occurs in traffic. To measure overall “satisfaction,” I obtain estimated attendance figures from NASCAR press releases and adjust sold-out events to hypothetical values that I create with my attendance model. I exclude races that were postponed in any manner. In total, I include 323 races from 2002 through 2012.

I provide a scatter plot to visualize the relationship between speed and attendance. Each dot denotes the pairing of speed (horizontal x-axis) and attendance (vertical y-axis) from races in the sample time period. I also include a green curve that marks the trend among these combinations.

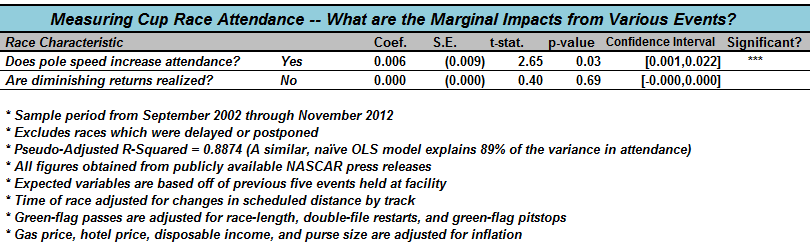

A visual inspection shows that there’s a positive relationship between speed and attendance (the lone exception – Bristol – is highlighted in pink). As the pole speed increases, attendance tends to increase; especially at higher speeds. But that’s a bit naïve. Attendance is heavily influenced, after all, by many other race characteristics. The local economy, location of the event, scheduling, prestige, and competition must be considered. To do so, I incorporate two measures of pole speed into my attendance model. The full table is reviewed in my original post on the attendance model. The chart below displays my test on the pole speed’s relationship with “satisfaction” after accounting for the twenty variables which help explain NASCAR’s changes in attendance:

After taking into account all of those economic, scheduling, and competition factors ; the pole speed — a proxy for Deford’s “speed” — does not exhibit diminishing returns. The first line possesses a significant coefficient of +0.006; that is, faster speeds are related to a jump in attendance, all other variables held equal. The second line (in which I use the square of speed) tests how speed increases at each point on the graph. If that number is positive, attendance increases at a greater rate for higher speeds. In contrast, a negative number represents the diminishing returns that Deford opines. Of course, the number falls at zero and is insignificant. This means that pole speed increases with attendance at a constant rate throughout the chart.

In conclusion, I visualize Mr. Deford’s theory that speed eventually grants little extra satisfaction for fans. I use race-level data from the previous decade to show that the actual relationship between pole speed and attendance does not exhibit diminishing returns. Finally, I use regression modeling to finalize that the writer’s theory does not exist in NASCAR’s Cup Series. While I find my contribution compelling, I don’t think it necessarily overturns Mr. Deford’s theory. After all, a point will inevitably be reached in which fans don’t find extra speed as more fascinating — we just haven’t witnessed it yet.